One afternoon at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, I walked into a room of paintings by Robert Ryman. Ryman’s white paintings hung on white walls under white lights, and there was almost too much daylight coming in. The guards at the museum wandered about wearing corporate bright red jackets and whenever I caught sight of one as I approached Ryman’s delicate white paintings, the brightness of the clothing would catch my eye and leave intrusive turquoise after-images hanging in the air between me and the art on the wall.

Ryman, who has died aged 88, himself worked at the MoMA in New York as a guard for seven years, after moving to the city in 1952. Born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1930, Ryman studied music before being enlisted, and was in a reserve army band during the Korean war. Moving to New York to study under jazz pianist Lennie Tristano, Ryman played hard bebop, influenced by Charlie Parker and Zoot Sims, taking the museum job to support himself. He knew nothing about painting. At MoMA he not only got to know the paintings of the abstract expressionists, but also fellow part-time museum guards Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin and Al Held. All three would become associated with minimal art in the early 1960s, though Ryman insisted he was not part of any movement. In 1961, Ryman married critic and curator Lucy Lippard (they divorced a few years later), and later got to know Eva Hesse and other artists in the downtown scene.

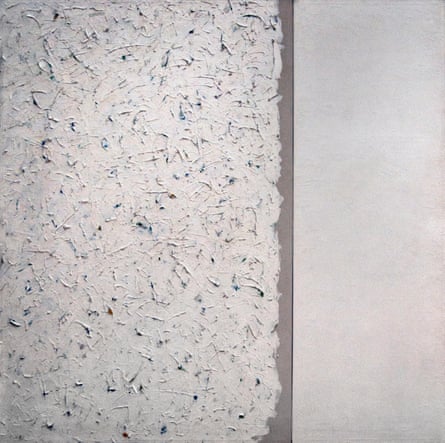

Ryman began painting in his apartment in the mid-1950s, often beginning with a colour that was then overpainted in a rime of biscuity, trowelled white marks. Some paintings were unstretched, on uneven scraps of linen. Some were explosive, or almost like coughs, or discarded paint rags or scraps that had been used to test a colour of a particular consistency of paint. Flecks of colour and the odd worm of paint, straight from the tube, curled from the mass of mostly white pigment. It was as if Ryman was trying to understand how layering and mixing, texture and touch could come together on a surface as an accumulation of actions and traces. They were very nearly not paintings at all, but a sort of residue, or an unfinished chain of thoughts that had just petered out, dwindled to a gasp or a sigh. Each painting was like an excerpt or an interruption, a barely begun jazz solo that had faltered to a stop. They are delectable things, all the better for being so truncated. Ryman, from the start, had a great touch. He also knew when to stop.

John Coltrane, talking to Miles Davis, admitted that he didn’t know how to end his increasingly lengthy solos. “Try taking the fucking horn out of your mouth,” Miles advised. Ryman was working out not just when to stop, but how to begin, and what it was that made a painting. I think he was asking not just what a painting was but when it was that his accretions of paint might become a painting, one thing leading to another like an improvised solo, and at what point to lift his brush from the canvas. It was all part of what has been called “the process of the process” in Ryman’s art.

There is a sense of suddenness about Ryman’s early work, a feeling of arrival. Sometimes these paintings were completed with a cursive signature or just his initials, and a date, which had the appearance of yet another form rather than a self-regarding authorial flourish. Ryman was taking painting apart to see how it worked, then reassembling it from degree zero. The support. The surface. The spread of one material over another. The limits. Whether to paint to an edge or to contain and constrict. What the boundaries are and where they lay. To paint to an edge or to overrun – like a cartoon character who keeps running till they realise they are already scrabbling in mid-air. He always came back from the brink. This is why his paintings are both so quiet and so exciting.

What Ryman focused on throughout his career was as much painting’s materiality as image-making, which for him appears to be a result of process and a series of considered actions. Material became a matter of the sheering and adhering of surfaces – lacquer or casein-based paints, oils and acrylics on wood or paper, canvas or metal. Gloss and matte-ness, thickness and thinness, evenness and churnedness. He worked his fields of white, walked their fences with his brush and his eye.

Ryman worked with white, and the different kinds of whiteness different paints and pigments produced throughout his career. Lead, zinc, barium and titanium, chalky whites and hard industrial whites, silky whites and bone whites, kitchen whites and shroud whites, numinous whites and dead whites. Whites that seem to spread outward and emit light as we look and whites to fall into. The variety of their opacity, depth, brilliance and dullness all interested him. We apprehend them all differently, and differently again depending on the materials they are painted over and how they are applied, what their binders are and how much they are diluted all make a difference.

Sometimes, looking at a Ryman is like looking at light coming in through a white window blind, its qualities changing through the day. He makes you focus, not least on your own looking. White marks squirm over rust-coloured metal and spreads softly like snow over a square. The square became as integral to his art as whiteness. He even considered the way a painting might be affixed to a wall as part of its make-up. My eye skates his surfaces, founders in them, get snagged on a row of staples and trips on a ridge of built-up pigment where the masking tape has been. These everyday details are integral to Ryman’s art. You can never forget its materiality, the fact of its manufacture (Ryman did everything himself, and never had assistants). He once described the sensation he was after as a soft, quiet experience. “It has to look easy,” he said, “That feeling like it just happened.” Ryman also said that the real purpose of painting is to give pleasure. Which it did, and does.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion